CLAIMING IN THE SHADOW OF LEGAL PLURALISM

Oleh: STIJN CORNELIS VAN HUIS (Januari 2026)

In my article: “ The Shadow of Legal Pluralism in Indonesian Islamic Courts: Child and Spousal Maintenance” published at the Indonesian Journal of Socio Legal Studies (2024), I explore the concept of legal pluralism and its impact on post-divorce maintenance claims in Indonesian Islamic courts, using the frameworks of “bargaining in the shadow of the law” and “Naming, blaming, claiming” in my analysis.

Legal pluralism refers to the coexistence of multiple normative frameworks—statutory law, Islamic law, and customary law—within a society (Beckmann 1981). “Bargaining in the shadow of the law”, first coined by Mnooking and Kornhauser in 1979, concerns out-of-court negotiations and how these negotiations are influenced by the legal position of the parties and probable outcomes of court cases would the negotiations fail. “Naming, Blaming, Claiming” refers to the renowned article by Felstiner, Abel, and Sarat (1981) where they treat claiming as a process and show how various factors in this naming-blaming-claiming process influence (non-)claiming behavior.

I argue that legal pluralism creates a complex interplay between different normative frameworks, shaping the behavior of all actors involved in the maintenance claiming process. In my article I extend the concept of “bargaining in the shadow of the law” to “bargaining in the shadow of legal pluralism,” where negotiations are influenced not only by statutory law but also by religious, customary, and cultural norms and values. This plural-legal context often places women in a disadvantaged position, limiting their ability to claim and enforce their post-divorce rights effectively.

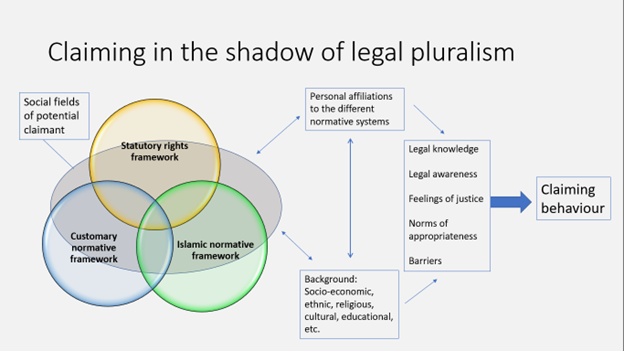

The factors that influence claiming behavior are summarized in the following figure:

Source: The Shadow of Legal Pluralism in Indonesian Islamic Courts: Child and Spousal Maintenance

Keebet von Benda Beckmann (1981,1985) argued that legal processes should be researched comprehensively by investigating the characteristics and dynamics of disputes in pre-trial, trial, and post-trial phases. For each phase we should investigate the different social fields involved, the normative frameworks that are at play in those social fields, as well as the entanglements between the different social fields. Therefore, I assumed that in the context of Indonesian Islamic courts, norms and values of the normative frameworks influence the claiming behavior of litigants as well as the behavior of judges, litigants, and communities during pre-trial, trial, and post-trial phases of maintenance claims.

Through analysis of data collected during two years of research in Cianjur and Bulukumba, I found that bargaining in the context of post-divorce maintenance the shadow (norms, values, and practices) of legal pluralism influences women’s claiming behavior in multiple ways.

- Pre-Trial Phase:

- Women’s decisions to file maintenance claims are influenced by the plural-legal environment they live in, where statutory rights often overlap with Islamic and customary norms.

- Cultural norms, such as reliance on kinship networks and expectations of passivity and acceptance (ikhlas), discourage women from making formal claims.

- Women often perceive court processes as cumbersome and avoid claiming their rights, even when they are aware of them.

- Trial Phase:

- Islamic courts emphasize negotiated agreements over strict adherence to statutory law, reflecting the influence of traditional Islamic legal culture.

- Judges often pressure women to accept lower maintenance amounts offered by their husbands, citing concerns about enforceability and the need for mutual agreement.

- The court’s preference for negotiated outcomes is shaped by the belief that agreements are more likely to be implemented than court orders.

- Post-Trial Phase:

- Court orders for maintenance are often unenforceable, and ex-husbands frequently fail to comply.

- Women rarely seek enforcement of court orders, relying instead on their kinship networks for support.

- The weak implementation of court orders in the post-trial phase influences judges’ behavior in the trial phase, as they aim to secure agreements that might have a higher chance of being honored.

Based on the above analysis, I conclude that the maintenance claiming behavior of women is not only influenced by cultural preferences for agreements and traditional gender-biases that reject assertive women claiming their rights within communities and Islamic courts, but also by the weak normative and persuasive force that maintenance court orders have within society. Overall, this “shadow of legal pluralism” causes a disadvantaged bargaining position of women vis-à-vis their ex-husband when they attempt to claim their statutory post-divorce rights through a court process.

References

Huis, S. C. Van. 2024 “The Shadow of Legal Pluralism in Indonesian Islamic Courts: Child and Spousal Maintenance.” The Indonesian Journal of Socio Legal Studies 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.54828/ijsls.2024v4n1.4

Benda-Beckmann, K. von. 1981. “Forum Shopping and Shopping Forums: Dispute Processing in a Minangkabau Village in West Sumatra.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 13 (19): 117–159.

Benda-Beckmann, K. von. 1985. “The Social Significance of Minangkabau State Court Decisions.” The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 17 (23): 1–68. doi: 10.1080/07329113.1985.10756286.

Felstiner, W. L., R. L. Abel, dan A. D. Sarat. 1980. “The Emergence and Transformation of Disputes: Naming, Blaming, Claiming . . .” Law & Society Review 15: 631.

Mnookin, Robert H., dan Lewis Kornhauser. 1979. “Bargaining in the shadow of the law.” Yale Law Journal 88: 950–997.

Comments :